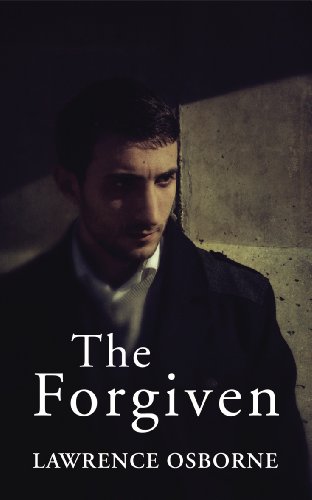

Where to start with this sumptuously descriptive novel dripping with lusciousness and foreboding? The background setting of Morocco is an intrinsic character that fluently comes to life through Lawrence Osborne's writing. Whether it is the landscape, the characters, the ambient temperature, the fossils or the people - both local Moroccans and Westerners whose lifestyles and values pit themselves against each other - everything is bathed in a terracotta hot red, set against the desert and mountains of the country. The food is richly described from the McVitie's crackers slathered with majoun (a mix of kif, dried fruits, nuts and sometimes fig jam) to the couscous "sweetened with sugar and lines of melted cinammon" to "almond breewats" all washed down with Santenay and Tempier Rose.

Jo and David Henniger are motoring down to the ksour, owned by Dally Rogers Margolin and his partner Richard Galloway at Azna, with the prospect of a weekend of hedonism with the rich and powerful from around Europe and America, billed as "the best party East of Marrakech". It is a dark night, the road gives off its accumulated daytime heat, the stark shadows rise up against the mountains. Suddenly, David, with a high level of alcohol in his blood, hits one of two locals, Driss, and kills him on the spot. His companion Ismael heads for the hills as the Hennigers step out of the car to assess the damage.The story expands from there as the cultures of the party people from Europe and America, and the indingenous peoples, the Berbers, weave an unforgiving path. The impact of the tragic incident reverberates into the hedonistic thrum of the party weekend, and forgiveness and revenge vie with each other, as the individuals all respond in their own unique way to events.

The author clearly knows the country really well and the research peppers the pages of the novel. We learn, for example. that fossil mining is a huge industry in the country and each tribe deals in different and specific fossil-types - only the black market dealers cross the lines. For now, though, enough of our eulogies, and over to the author himself for a few words:

TF The book brings the rugged countryside and people of Morocco to life. A really red burning, hot and brooding sense comes through your writing. You clearly know the country very well, how has that come about?

LO I began traveling to Morocco many years ago, spending winters alone in a place called Essaouira. It's still place I love and that I go back to. When I was younger I used to like taking buses all over the country, it was a way of being alone for weeks on end during spells of unhappiness. Then, later, I made some trips into the deep desert to collect fossils at Jbel Izzomour and Alnif, places that are far off the road maps, and the solitude came to be of a different order. On one trip I went to Erfoud with a French girlfriend and for weeks we argued and fought during endless sandstorms and, I think, the first seeds of the novel were implanted.

TF What was you inspiration for the gripping and black storyline of The Forgiven?

LO It was a story told to me by my then-agent Emma Parry during lunch one day in New York. It was, apparently, true. I changed a few things, of course, and created my own ending and themes....but when I heard it I thought "But I know those places from years ago." I had never written anything about Morocco, not even a travel piece. I never wanted to do any travel writing about it - it meant too much to me. But the story immediately resonated with me. I never hesitated, I started writing it that night.

TF You clearly show how

two cultures struggle to live side by side – the Westerners bring moral

standards that are very different from those of the indigenous people in

Morocco. How smoothly do the cultures co-exist in practice?

LO I see that the Washington

Post has just published a map showing the most and least welcoming countries on

earth and Morocco is rated as the third most welcoming. Very well. But there is

more to it than that. There is suspicion and distance too and I think two

cultures will rarely lie down side by side easily. I live in Thailand, which

was also rated high in the Post piece, but Thai attitudes to westerners are not

simple either. When you live in a place for a while you see that the apparent

harmonies are often just expediencies that can easily decline into paranoia and

defensiveness, not to mention exploitation.

TF Nicholas Lezard describes you as “a master of the high style” when he refers to your book: The Wet and The Dry: A Drinker’s Journey. We very much enjoyed your writing style in The Forgiven. How did you initially come to writing?

LO I have been working as a journalist since I

was very young and writing non-fiction books, but apart from a novel that was

published when I was 27 I would say I came rather late to fiction...there was a

long gap but I was struggling with the form all the time, largely

unsuccessfully. It doesn't come easily to me. I had to rewrite The Forgiven over a period of several

years before it was accepted by anyone. It took so long because I needed to

work out my own prose attitude and style dealing with the things I wanted to

explore - the relations between men and women, for one thing, and the way

landscapes create story and character, the relation between western personality

and non-western - a theme that fascinates me. I knew what I wanted to explore,

and the simple elegance and suppleness I needed, but I didn't have the means to

do it. I am not sure I do have it now, but it seems to be crystallizing.

TF What are

you working on now?

No comments:

Post a Comment